Object monitor

Synchronization is built around an internal entity known as the intrinsic lock or monitor lock. (The API specification often refers to this entity simply as a “monitor.”). Intrinsic locks play a role in both aspects of synchronization: enforcing exclusive access to an object’s state and establishing happens-before relationships that are essential to visibility.

Every object has an intrinsic lock associated with it. By convention, a thread that needs exclusive and consistent access to an object’s fields has to acquire the object’s intrinsic lock before accessing them, and then release the intrinsic lock when it’s done with them. A thread is said to own the intrinsic lock between the time it has acquired the lock and released the lock. As long as a thread owns an intrinsic lock, no other thread can acquire the same lock. The other thread will block when it attempts to acquire the lock.

When a thread releases an intrinsic lock, a happens-before relationship is established between that action and any subsequent acquisition of the same lock.

Locks In Synchronized Methods

When a thread invokes a synchronized method, it automatically acquires the intrinsic lock for that method’s object and releases it when the method returns. The lock release occurs even if the return was caused by an uncaught exception.

You might wonder what happens when a static synchronized method is invoked, since a static method is associated with a class, not an object. In this case, the thread acquires the intrinsic lock for the Class object associated with the class. Thus access to class’s static fields is controlled by a lock that’s distinct from the lock for any instance of the class.

Synchronized Statements

Another way to create synchronized code is with synchronized statements. Unlike synchronized methods, synchronized statements must specify the object that provides the intrinsic lock:

public void addName(String name) {

synchronized(this) {

lastName = name;

nameCount++;

}

nameList.add(name);

}

In this example, the addName method needs to synchronize changes to lastName and nameCount, but also needs to avoid synchronizing invocations of other objects’ methods. Without synchronized statements, there would have to be a separate, unsynchronized method for the sole purpose of invoking nameList.add.

wait(), notify() and notifyAll()

The Object class in Java has three final methods that allow threads to communicate about the locked status of a resource.

wait()

It tells the calling thread to give up the lock and go to sleep until some other thread enters the same monitor and calls notify(). The wait() method releases the lock prior to waiting and reacquires the lock prior to returning from the wait() method. The wait() method is actually tightly integrated with the synchronization lock, using a feature not available directly from the synchronization mechanism.

In other words, it is not possible for us to implement the wait() method purely in Java. It is a native method.

General syntax for calling wait() method is like this:

synchronized( lockObject )

{

while( ! condition )

{

lockObject.wait();

}

//take the action here;

}

notify()

It wakes up one single thread that called wait() on the same object. It should be noted that calling notify() does not actually give up a lock on a resource. It tells a waiting thread that that thread can wake up. However, the lock is not actually given up until the notifier’s synchronized block has completed.

So, if a notifier calls notify() on a resource but the notifier still needs to perform 10 seconds of actions on the resource within its synchronized block, the thread that had been waiting will need to wait at least another additional 10 seconds for the notifier to release the lock on the object, even though notify() had been called.

General syntax for calling notify() method is like this:

synchronized(lockObject)

{

//establish_the_condition;

lockObject.notify();

//any additional code if needed

}

notifyAll()

It wakes up all the threads that called wait() on the same object. The highest priority thread will run first in most of the situation, though not guaranteed. Other things are same as notify() method above.

General syntax for calling notify() method is like this:

synchronized(lockObject)

{

establish_the_condition;

lockObject.notifyAll();

}

In general, a thread that uses the wait() method confirms that a condition does not exist (typically by checking a variable) and then calls the wait() method. When another thread establishes the condition (typically by setting the same variable), it calls the notify() method. The wait-and-notify mechanism does not specify what the specific condition/ variable value is. It is on developer’s hand to specify the condition to be checked before calling wait() or notify().

Links

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/essential/concurrency/locksync.html

https://www.programcreek.com/2011/12/monitors-java-synchronization-mechanism/

https://howtodoinjava.com/java/multi-threading/wait-notify-and-notifyall-methods/

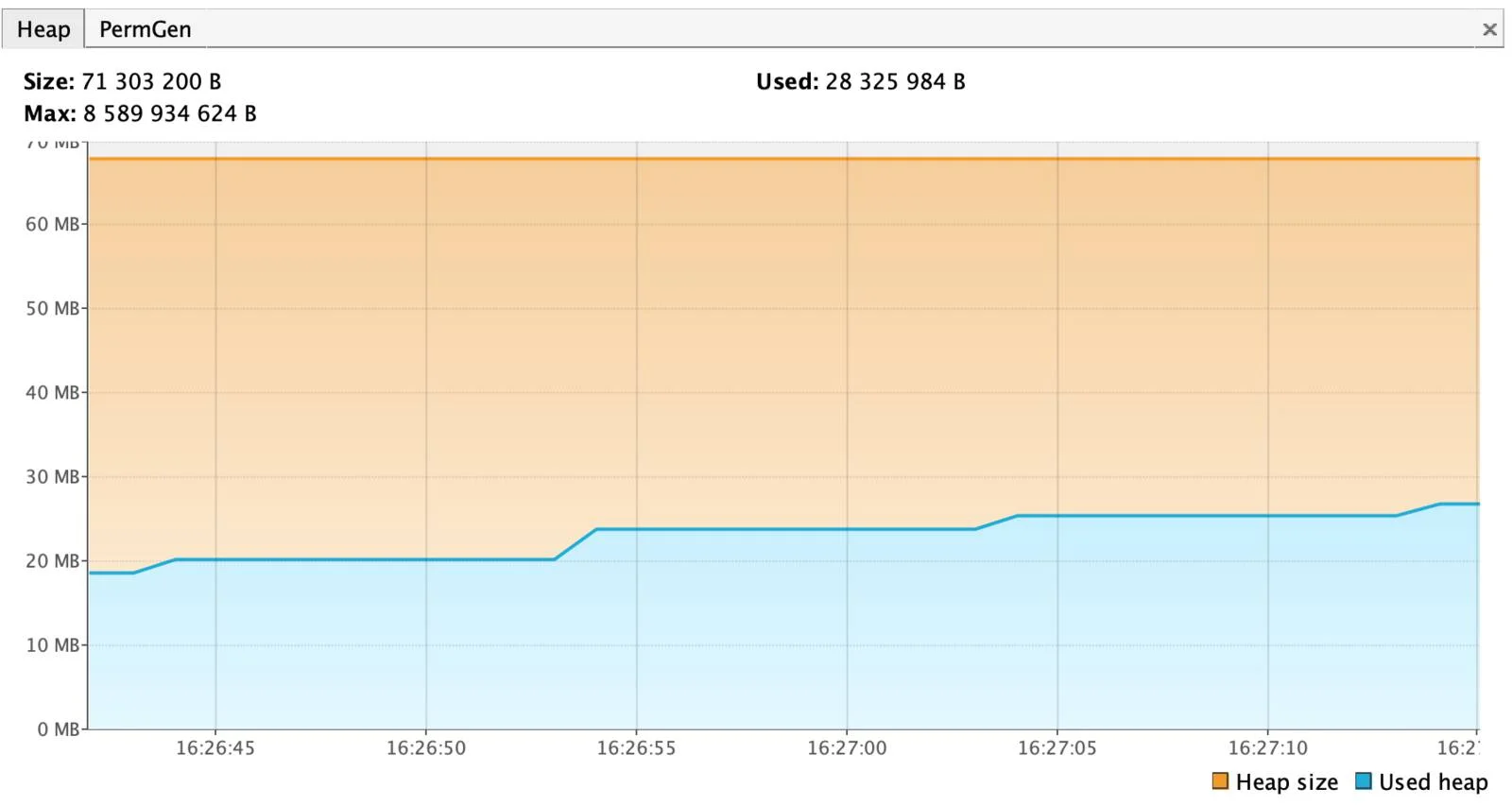

Java - java_memory_leak

Java - java_memory_leak